How to Handle Rare Radiation Complications

Urologic Complications After Radiation Therapy for Prostate Cancer

By: John Stoffel, MD

Prostate Cancer is the second most common malignancy that affects men after skin cancer. It is estimated that about 170,000 men are diagnosed with the disease each year. Depending on the stage and grade, prostate cancer can be managed with active surveillance, surgical removal of the prostate gland (radical prostatectomy), or radiation therapy. All interventions have different risks and benefits. In this article, we will discuss some potential complications in the urinary tract that can occur after radiation treatments.

Radiation for prostate cancer treatment can be either external or internal. External beam radiation is delivered from a machine outside of the body. Internal radiation treatments are commonly called brachytherapy, seed implants, or interstitial radiation therapy. This webpage from cancer.org (https://www.cancer.org/cancer/prostate-cancer/treating/radiation-therapy.html) reviews radiation types in more detail.

Urinary Symptoms

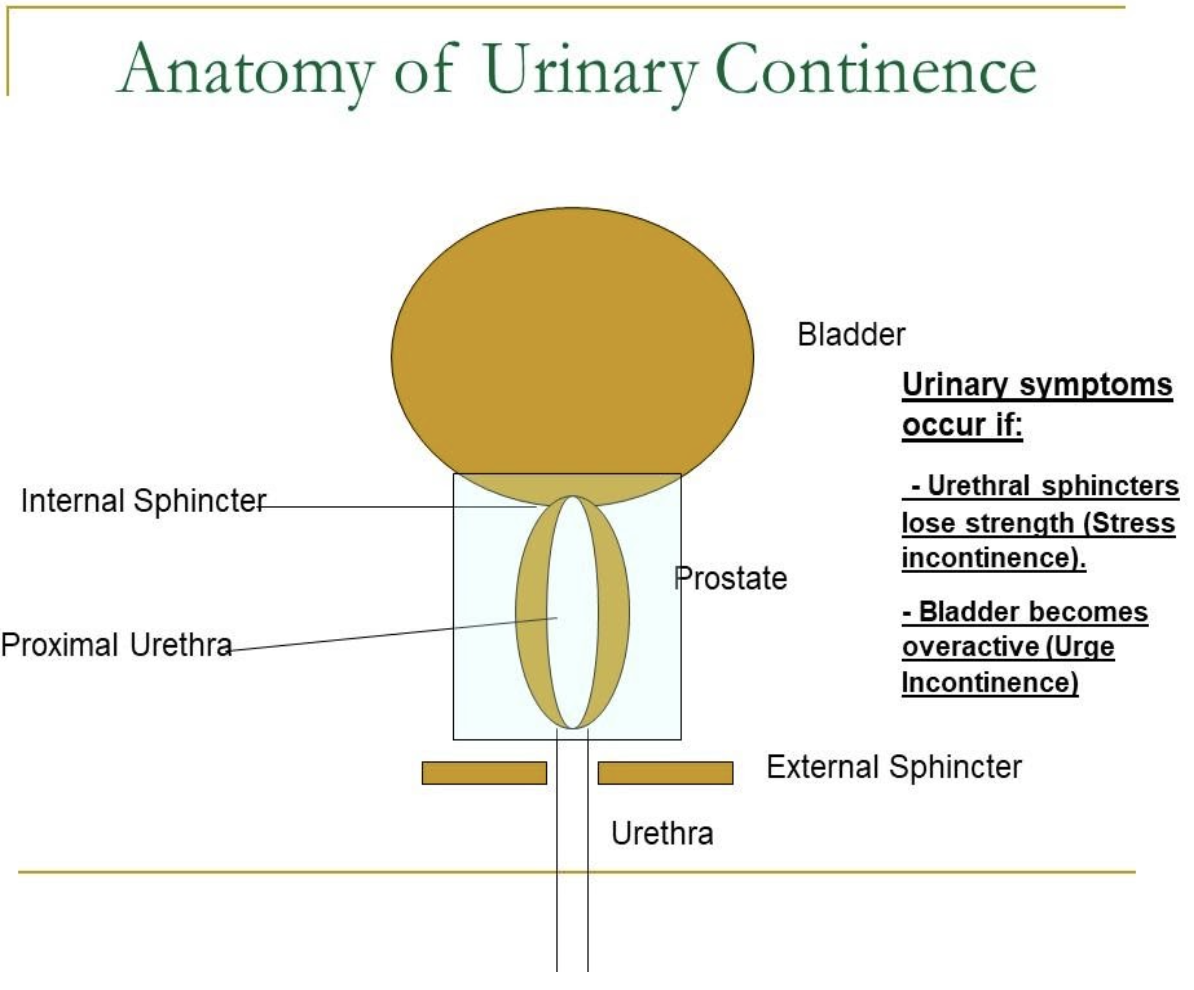

Radiation can cause urinary symptoms such as incontinence (leakage of urine). Depending on which part of the anatomy is affected, men can develop either stress incontinence or, more commonly, overactive bladder.

When radiation causes damage to the urinary sphincters, the urethra cannot close as tightly, and men experience leakage with activity. This radiation-induced stress incontinence, if severe, can be treated most effectively with an artificial urinary sphincter surgery. Men treated with perineal sling surgery for radiation stress incontinence do not generally see significant improvement, unlike men with stress incontinence caused by radical prostatectomy.

If radiation causes irritation or inflammation to the bladder muscles, men may experience urinary urgency, frequency, and inability to delay urination. These symptoms are effectively managed with medications that decrease the contractility of the bladder. One type of medication, anticholinergics (e.g., Toviaz, Vesicare, Enablex), can cause dry mouth and constipation. A different type of medication, beta-3 agonists, such as Myrbetriq, can raise blood pressure slightly.

Men who do not respond to medications could potentially benefit from botulinum toxin (botox) treatments to the bladder. This medication is delivered through a cystoscope into the bladder and can last for 6-12 months. This treatment has a 10-15% chance of causing urinary retention (inability to void), meaning the patient will have to be catheterized until the bladder paralysis wears off.

Alternatively, some men with refractory overactive bladder could benefit from neuromodulation. This treatment consists of stimulating the nerves carrying sensory information from the bladder to the spinal cord, which can cause a reflexive relaxation of the bladder. Neuromodulation can be performed as an implantable stimulator, which is placed in the operating room, or as a weekly stimulation with an acupuncture needle to the posterior tibial nerve in the leg for 12 weeks.

Urinary symptoms present later after radiation treatment, compared to men treated with radical prostatectomy. Whereas urinary symptoms appear within days after surgery, new urinary symptoms can present several months after radiation therapy is finished and in some patients could continue to increase in severity.

Urinary Obstruction from Radiation Scarring

Radiation can occasionally cause a buildup of scar tissue at the junction between the prostate and bladder, called the bladder neck. This is caused by inflammation and a loss of blood supply. As scar tissue builds up, it becomes more difficult to urinate. The scar tissue can ultimately progress such that men cannot urinate. They end up retaining urine in the bladder. This scar tissue does not respond to medications or physical therapy treatments. Most men with symptomatic obstruction at the bladder neck from radiation scarring will require a minimally invasive surgical procedure called a cystoscopy and bladder neck incision/dilation. This procedure is usually performed in the operating room as an outpatient surgery. After the scar tissue is incised, a catheter may be placed for a few days to stabilize the scar. If deep cuts are needed, there is a risk of incontinence. Some men may need to keep passing a catheter through the penis into and out of the bladder daily to continue to dilate this scar tissue. This is called intermittent self-catheterization. Even with these treatments, there is a significant risk of scar recurrence. A repeat cystoscopy/incision may be performed, and a steroid may potentially be injected into the scarred area, but these methods do not have very high success rates.

Men with complete obstruction of the urethra from radiation scarring may benefit from a suprapubic tube. During this procedure, a small 2cm incision is made in the skin above the pubic bone over the bladder, and a small puncture is made in the bladder. A drainage tube, called a catheter, is placed through the puncture site, and the catheter is connected to a collection bag. Urine is drained continuously from the bladder through this tube. It remains in place and is changed monthly. An indwelling suprapubic tube increases the risk of urinary tract infections. If urinary tract infections are occurring frequently, men may be asked to irrigate the suprapubic tube daily with an antibiotic solution called gentamicin. The suprapubic tube is usually changed monthly. Suprapubic catheters are preferable to standard catheters in the penis. Compared to an indwelling catheter, a suprapubic tube is generally more comfortable and causes less damage to the penis.

Alternatively, some men with complete obstruction of the bladder neck opt for a surgical procedure called a "bladder augment and continent catheterizable channel." A bladder augment surgery is performed in the operating room under general anesthesia. The procedure can take 3 to 5 hours, depending on the complexity. During this procedure, the bladder is made bigger. The surgeon first isolates 30 to 45 cm of the intestine in the abdomen. The GI tract is then reconnected, so that normal bowel function is restored. Your surgeon then sews the isolated segment into a "patch" and connects the "patch" to an opening in the bladder. In other words, think of this as building an addition onto a house (bladder) to create a larger space for urine storage. A continent stoma is created during the bladder augmentation so that men can drain the augmented bladder. A continent stoma is a small tube made out of the appendix, bladder, or intestine that connects a small opening in the abdomen to the bladder. Men can insert a catheter into this opening, to access the bladder, and drain the urine. The continent stoma has a biologic valve in it to prevent urine from leaking. This surgery carries risks of leaking urine from the stoma (10%) and bladder stones (30%).

Fistulas in the Urinary Tract

Although uncommon, some men can develop a hole between the prostate and the rectum after radiation therapy. This hole, called a fistula, causes men to leak urine from the rectum during bowel movements. Most fistulas do not close spontaneously. Men with recto-urethral fistulas are usually first treated by placing a suprapubic tube to divert urine from the bladder and a colostomy to divert stool from the rectum. After the fistula matures (3-6months), some men opt for a surgical repair in which the prostate and rectum are separated, the respective holes closed with sutures, and a muscle flap from the leg is placed between the two closed organs.

Radiation Cystitis

Rarely, radiation may cause severe inflammation within the bladder. This may present with pain in the abdomen, pain with urination, urinary frequency, and/or blood in the urine. Over time, the bladder may lose capacity and decrease in size. Initially, men are treated with medications to decrease bladder overactivity and reduce inflammation. Men with significant bleeding may also need to have a procedure performed in the operating room to cauterize the bleeding vessels. If bleeding and urinary symptoms continue to progress, men may attempt to irrigate the bladder with solutions that attempt to coagulate bleeding vessels. These procedures rarely result in long term cure. At this stage of radiation cystitis, many men consider hyperbaric oxygen treatments. These treatments consist of sitting in an oxygen-rich chamber. This increased oxygen pressure can decrease inflammation caused by radiation and sometimes heal the bleeding vessels. If this is not successful, most men pursue surgical procedure to remove the bladder and divert urine into a urostomy. The urostomy is a small segment of intestine that collects urine from the kidneys. The urine drains continuously through an opening in the person's side called an ostomy. A bag is placed over the ostomy and is changed approximately two times per week.

Ureteral Obstruction after Radiation Therapy

Men with radiation cystitis may also develop obstruction of the ureters, the tubes which connect the kidneys to the bladder. If the ureters become obstructed, urine cannot drain from the kidneys, and the kidneys can become damaged. If left untreated for long periods of time, the kidneys can fail, and dialysis is needed. Most ureteral obstructions are initially treated with ureteral stents. These stents are small plastic tubes, which, when inserted into the ureters, allow urine to drain from the kidney to the bladder. The stents are changed anywhere between 1 – 12 months, depending on the type of stent used and severity of the obstruction. If stents are not effective in unblocking the ureter, surgical reconstruction may be needed. This may entail cutting the ureter above the blockage and sewing it to a different location on the bladder (reimplant), or building a new ureter out of intestine (ileal ureter). If the obstruction occurs in the setting of radiation cystitis, a bladder augment, or a cystectomy/urostomy may be needed.

Conclusion

If you begin to experience urinary symptoms after radiation therapy, then it is important to be aware of the fact that the ideal treatment depends on the exact cause and severity of the symptoms. Urinary symptoms from radiation therapy are somewhat rare and usually develop long after the therapy has been administered. If you do begin to experience symptoms, then it is important to know all of your options and to be proactive with your doctor for the best chance of preserving your quality of life.

John Thomas Stoffel, MD is Professor of Urology and Chief of the Division of Neurourlogy and Pelvic Reconstruction at the University of Michigan, Department of Urology. Prior to attaining this position, he graduated from the Washington University School of Medicine in 1997, completed his residency at Massachusetts General Hospital in 2003, and completed a fellowship for female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery at the University of Michigan. He has written over 110 papers on the topics of neurogenic bladder treatment outcomes, urinary incontinence, and ureteral reconstruction.