Understanding Your Bone Scan and Other Bone Imaging

By the PCRI Staff

Understanding your medical records is an essential part of patient empowerment. (For more on this subject, please see the 2010 PCRI Insights article titled “Making the System Work for You: Principles of Empowerment”.) In connection with the article on Alpharadin (Radium-223) on page 9, this piece will focus on understanding bone imaging better, with a primary focus on the conventional bone scan.

Without an understanding of your medical records, you are likely to research the term “prostate cancer” alone, which can lead to a bottomless well of impersonal information. With some understanding of your records, you will learn to research prostate cancer in context of your own biology – your own pathology, PSA pattern, imaging results, and prostate size, to name a few factors.

This research leads to the understanding you need to develop questions for your physician(s). The quality of your understanding will shape the quality of those questions, and the quality of your questions will determine the quality of your answers. Therein lies empowerment.

For years, PCRI has focused on the fact that no two prostate cancers are alike. Research has taught us that new science is likely to discover more and more diversity (1). Isolated characteristics may be the same, but many characteristics are different.

Medical records provide facts, details and specifics that illuminate the characteristics of your cancer. Imaging of the bone is one such medical record. The most common type of bone imaging is the standard bone scan, but F18 (and sometimes FDG18) PET scans have also seen more widespread use in recent years. In addition, CT, MRI and X-ray are occasionally used for supportive or backup imaging of bone.

Besides being common protocol, the bone scan is also the imaging utilized in Alpharadin clinical trials. It involves an injection made up of a “radionuclide” (low-dose radiation), plus a “pharmaceutical” – a simple definition for a “radiopharmaceutical” (2). The name of the radiopharmaceutical used in bone scans is Technetium 99m. This term is often seen in the title of the bone scan report.

Bone Scans & PSA

There is ongoing debate over what a PSA level should be before ordering a bone scan, especially in context of health care costs. There have been studies, arguments and statistics on this topic, and despite variations in opinion, one thing remains clear: The patient should always be the most important consideration in the decision.

To editorialize for a moment, I personally believe that PSA alone should not determine whether a prostate cancer patient should have a bone scan. We know, for example, that higher Gleasons often make less PSA. NCCN guidelines support this by including both Gleason and clinical stage in the decision of whether or not to scan (3).

I know someone who is a terrific advocate, whose husband had a bone metastasis with a PSA of 1.5 at diagnosis. But his Gleason was 9 (5+4). The bone metastasis was validated with pathology from needle biopsy – so there was no question that imaging found a cancer metastasis. I was glad they did not make their decision to do scans based on PSA alone. The patient’s whole biology was taken into consideration.

I have a Helpline caller who chose prostatectomy as his initial treatment. His cancer was more widespread at surgery than originally thought, and his Gleason turned out to be 8 (4+4). His PSA crept up quickly after surgery, and with a PSA of 2.1 he had a positive bone scan. I was glad he did not make his decision to order a bone scan on PSA alone, and found his metastases early. He has become a very empowered patient who is now doing extremely well.

After 12 years of doing this with my own husband, and after 10 years of working for PCRI, I believe that making the decision to image – or not image – is more scientific and reasonable if the entire biology is taken into consideration, rather than the PSA alone.

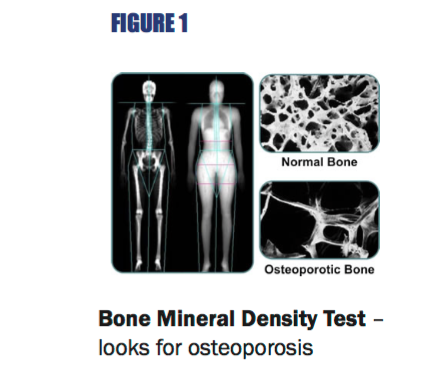

Bone Scan vs. Bone Density Scan

It is important to note that a bone scan, which looks for bone metastases, is different from a bone mineral density scan, which looks for osteoporosis. These two are often confused (See Figure 1, Table A and Table B).

FIGURE 1

Bone Mineral Density Test – looks for osteoporosis

FIGURE 1

Bone Scan – looks for cancer in bone

Who Interprets my Scans?

It is also important to understand that every medical imaging performed (BS, PET, CT, X-ray, MRI, etc.) is read by a physician, and a dictated written report is issued. This interpreting physician will be either a radiologist or a nuclear medicine physician.

So although the scan may be ordered by a urologist, medical oncologist or radiation oncologist, the physician who interprets the imaging is someone different. He or she is an M.D. trained in a different area of medicine (radiology or nuclear medicine), and does not see patients in a clinic. Their job is to read, decipher and translate imaging into a dictated written report, which they provide to your ordering clinical physician.

The difference between radiology and nuclear medicine is basically whether or not a radiopharmaceutical is used. These injections are designed to adhere to certain types of tissues (cancer being the most common), and reveal a spot or uptake in that area.

For example, the bone scan is nuclear medicine, and cancer in the bone is revealed as a “hot spot,” or excess uptake of the radiopharmaceutical. PET scans are also nuclear medicine, and there are many different types of radiopharmaceuticals used – which dictate the type of PET scan. F18 and FDG18 are currently utilized for bone imaging in the U.S. for prostate cancer.

A CT scan, on the other hand, may also involve an injection, but it is not a radiopharmaceutical, so CT is radiology, not nuclear medicine. MRI is radiology, even if an injection is used (gandolinium, feraheme, etc). Ultrasounds and X-rays are radiology.

A Radiologist is a physician who reads and interprets imaging – he does not treat patients with radiation.

A Nuclear Medicine physician also reads and interprets imaging, but works primarily with “Nuclear” imaging, which requires radioactive isotope injections, such as bone scans, PET scans, etc.

A Radiation Oncologist treats patients with radiation.

Written Report vs. Actual Images

The dictated written report is the medical record you can use to research your disease. There are also actual images (usually on film or CD), but these cannot be read accurately by an untrained eye.

The terms on these dictated written reports will be unfamiliar – but the definition of anything can be researched online. Google it, Bing it, Yahoo! it, or Ask Jeeves - doesn’t matter. Just search for the definitions. They are easy to access on the internet, and explanations can usually be found in simple language. If you don’t use the internet yet, this is a great time to start.

Why reading and understanding the basics of your bone scan report can be empowering:

• Correlating your imaging with PSA or CTC can help you understand your disease better. Does your imaging improve when your PSA or CTC improves? (PSA improvement usually precedes imaging improvement.) This may help you develop better questions moving forward in your treatments.

• Correlating imaging with pain can help you understand whether or not your pain is cancer-related. One fear many cancer patients have is that every new pain may be new cancer. If you know what your imaging says (and doesn’t say), then you have something objective to help you face those fears. Fear turns into understanding, and the new pain is often not cancer, but something else.

• How do you know if you are eligible for some treatments, such as Alpharadin? Or perhaps another clinical trial you are considering? Knowing what your bone scan says will give you the knowledge you need. Of course, this also needs to be discussed with your physician(s).

The idea here is not to know all the answers, but to develop better questions, which should lead to better answers.

To help you understand what your bone scan report means – and doesn’t mean – here are some explanations of what can be found on a typical report.

Sections of a Bone Scan Report

Title

The title of the bone scan document can have different terms.

In fact, sometimes it doesn’t even say “bone scan”, so this can be confusing. You may often see “Whole Body”, or WB. You will usually see a reference to the injection used (Technetium 99m), and may also see the term “Nuclear Medicine”. These are all common words in the title of a bone scan report, and no two titles are exactly the same. It seems odd, but it’s true.

Date

Always make sure you circle the date that your imaging was performed. This may sound simple and obvious, but it is often overlooked. If you can’t quickly find the date on a medical report, you can’t use it effectively.

Remember, you will keep your medical records now, but try to come back to them later. What important points do you want to access quickly?

Comparison

It is always important to have any imaging compared to previous similar imaging.

Bone scans should be compared to previous bone scans, because the change between two scans can tell you more than a single report can. If a previous bone scan was done at a different location, the current radiologist

reading your images may not have access to the previous bone scan, or even know it exists - unless you (the patient or advocate) show them. Make sure your bone scan, PET and any other imaging is compared to previous scans. This is usually indicated on the report, just under the title.

Findings

This is where the radiologist or nuclear medicine physician dictates everything he sees in paragraph form. There will be mention of unremarkable (normal) findings, suspicious findings and definitive findings.

A critical point to remember here is that no medical imaging is perfect. They all have different strengths and weaknesses, depending on (1) what the imaging is looking for, and (2) what part of the body the imaging is looking at. In the case of the bone scan, there will be “uptake” anywhere there is new bone formation. This is not always 100% cancer.

Uptake will also show where there is degenerative disease, previous fractures and sometimes arthritis. A good example of this is bone scan uptake in the knees or feet that are common arthritic changes, but negligible for cancer metastases. All of this will be discussed in the section on your report called “Findings”. Read it carefully, and research anything you don’t understand before you ask your physician(s).

One of the most important statements in this section can be if something on the bone scan looks suspicious, but not definitive. If so, follow-up imaging such as MRI or X-ray is usually suggested. If follow-up imaging was suggested, but somehow not carried out, this is an important question to ask your physician(s) about. I have seen this happen more than once.

Impression

This is where the radiologist or nuclear medicine physician dictates what he sees in an abbreviated summary, and basically consists of the significant conclusions.

Here are some common words you will find (See Figure 2 and Table B):

Cervical or C1 – C7. These are the 7 spinal vertebrae in the neck.

Thoracic (also Thorasic) or T1 – T12. These are the 12 spinal vertebrae in the middle/main part of the back.

Lumbar or L1 – L5. These are the 5 spinal vertebrae in the lower back.

Sacrum or S1 – S5. These are the 5 spinal vertebrae in the tailbone.

Other bones mentioned may be the ilium (pelvic bones), femur (thigh bone) and humerus (upper arm bone).

Obviously there are more, but they are too many to mention. All can be researched online.

Osseous – another word for bone.

Blastic/Sclerotic – the type of bone metastasis that looks like a buildup of bone, or a bump. The overwhelming majority of prostate cancer bone metastases are blastic (or sclerotic). This is the type of metastasis that Alpharadin can treat.

Lytic – the type of bone metastasis that looks like a loss of bone, or a dent or hole. Most other cancers have bone metastases that are lytic. This is the type of metastasis that Alpharadin cannot treat effectively.

"A critical point to remember is that no medical imaging is perfect. They all have different strengths and weaknesses."

Signature

The radiologist or nuclear medicine physician will sign the report. Also look for page numbers – it may say “page 1 of 2” or “page 1 of 1”, etc. Make sure you have all the pages to your dictated written report from your bone scan.

PET Scan for Bone

In recent years, PET imaging and PET/CT-fused imaging have become more commonplace for imaging bone metastases for prostate cancer. In some clinics, it has replaced the bone scan.

This may be temporary, as the future of insurance reimbursement is uncertain. Currently, Medicare has been paying in most areas of the United States because of a National Oncologic PET Registry (NOPR) for F18 (or FDG 18) PET scans which started in January 2011. (4,5)

To date, the wording in the NOPR coverage for PET in prostate cancer reads like this (6):

There are many different types of PET scans, because the type of scan depends on the type of radiopharmaceutical administered. In other words, an F18 PET scan is different from an FDG 18 PET scan, because the injection used is a different radiopharmaceutical. These are the two types of PET covered in the NOPR. If you had a PET, it is likely one of these 2 types.

Studies show that F18 and/or FDG18 PET scans have better accuracy than traditional bone scan in finding bone metastases in prostate cancer. (6)

Follow-Up & Additional Bone Imaging

If the physician who read and signed your bone scan report found something that he thought to be suspicious, but not definitive, he may suggest ordering additional imaging to rule out cancer metastasis. You will probably find different clinical opinions on what type of imaging is most useful, or even on when follow-up imaging is necessary. But here are some pointers that can help in your understanding.

CT Scans – CT or CAT scans can also read bone. In years past, a CT used to image a prostate cancer patient often made no mention of bone findings, and simply commented on soft tissue and lymph nodes.

It does seem there is a pattern of more radiologists reading what they see in bone on a CT than in previous years. This can be a helpful correlation with the bone scan. If the CT was performed on the same day as the bone scan, it is a good question to discuss. This is probably common. If a PET scan is used to image bone, a CT is often used in conjunction with the PET.

MRI –Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) is sometimes suggested for follow-up imaging. Since MRI can visualize bone marrow well, it is sometimes ordered to image suspicious findings in the spine.

X-ray – Also called “plain films” or AP, X-rays are occasionally ordered as follow-up imaging if a bone scan finding is suspicious but not definitive for cancer.

You may never understand your bone scan report like a physician – I don’t. But you can certainly understand it as an empowered patient – I do.

Don’t be intimidated by large words that look like another language, because they’re not. They change from foreign to familiar when you find the definition.

Remember that empowerment lies within these records, because that’s where your biology lies. Keep in mind that the quality of your answers depends on the quality of your questions. Remind yourself that you’ve done greater things than learning to understand medical records – so you can do this too. Remind yourself that empowerment quenches fear, and understanding is the road to empowerment.

References:

(1) Taylor, et. al. Integrative genomic profiling of human prostate cancer. Cancer Cell 2010 July 13; 18(1): 11-22

(2) Nuclear Medicine - Society of Nuclear Medicine glossary

(3) NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines, Prostate Cancer. Version 2. 2012

(4) Segall G., NaF PET/CT Bone Scans, Presentation 2011

(5) National Oncologic PET Registry: Information for Patients,

(6) National Oncologic PET Registry: FCG Indications: Cancer and Indications Eligible for Entry in the NOPR

Originally posted in PCRI Insights Magazine, May 2012